Search for successor to Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi intensifies as the country looks towards a strong leadership amid the escalation tensions in the Middle East - Though Raisis son is close to supremo Ayatollah Al Khamenei, the clergy might chose the senior most among its leaders as its against the dynastic principle

Search for the successor to late President Ebrahim Raisi begins to end

the uncertain future of a leaderless Iran following his tragic death in a

helicopter crash in the northwestern hills

By Ashe Ayer

A successor to late President Ebrahim Raisi, who died in a copter crash

in north western region of Iran, not only means a step of ascension to the

presidency but also to the next inline to the country supreme leader position

now occupied by Ayatollah Al Khamenei.

With Iran plunged into a cold war with USA and Israel since the Israel

Hamas war, accused of aiding and abetting with the militant outfits from the

hamas to Hezbollah to the houthis in yemen, , the country needs to fill up fast

the vaccum created by the death of Ebrahim Raisi.

Conspiracy theories are afloat about the mysterious and sudden death

Raisi in the copter crash soon after Iran inked a 10 year agreement with India

to run the pivotal Chabahar port to which the Indian navy will have access.

Fingers are being pointed at Pakistans ISI, Israels Mossad and USA’s CIA as

possible conspirators and co conspirators or a single conspirator.

However outlandish the theory might sound, but its gaining credence in

the Arab world, to which Iran does not belong in ethnicity, as it’s a Persian

kingdom turned religious dictatorship.

Religious doctrines override any political doctrines in the country and

its pursuit of a nuclear power programme is fraught with suspicion by the Western

World that it has led the USA, its arch enemy, to impose sanctions an oil

embargo on it.

The death of Ebrahim Raisi poses significant questions, not just over

his own successor but also that of Iran's supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali

Khamenei. The leader has to be strong to

take on the might of USA, Pakistan and Israel all at one go and strengthen ties

with Russia and China and keep its trade lines open with India . India is one

of its biggest buyers of Iranian oil.

The sudden death of a leader will shake any country, but the crash that killed President

Ebrahim Raisi comes at a particularly precarious moment

for Iran and the Middle East as a whole.

Though Ebrahim raisi is not exactly from the clery but more from the judiciary,

he still ruled with an iron hand to put down domestic disturbances when he had

ov er 2,000 people opposing the religious doctrines he forced on the people.

Women were upset with him for forcibly asking them to wear the hijab, the head

scarf, while going out in public.

Women, according to western media, actually celebrated his death as they had called him the

“Butcher of Tehran “ much like the Nazi general was called the “Butcher

of Riga”.

The Nazi butcher of Riga was hunted down by the Mossad. He's alleged to have exterminated 30,000 jews.

The Islamic Republic is a regional giant that can ill afford a wobble at

the topm says a CNN analyst. On the overseas front , Alex Smith says , it is

engaged in a shadow war with Israel that

has come terrifyingly close to spiraling into an open regional conflict. At

home, it is grappling with a long-running economic crisis

that’s been joined by social turmoil, as brutal protest

crackdowns have caused a widening chasm between

the ultraconservative religious elite and the more liberal youth.

Raisi, 63, was seen by many as a pliant figurehead, chosen for his

loyalty to Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran’s aging supreme leader.

Former Western officials and experts said it was unlikely the death of

Raisi would trigger major changes in how the theocratic government handled

international or domestic issues, including Tehran’s long-established hostility

to the U.S. and its support of Hamas and other proxy groups across the Middle

East.

“I don’t expect any major sort of fundamental shifts in domestic or

foreign policy,” said Alex Vatanka, senior fellow and the founding

director of the Iran program at the Middle East Institute think tank in

Washington. Raisi has “always been a yes man.”

While this may not change any immediate policies — foreign or domestic —

many observers believed him to be a front-runner to replace Khamenei, 85, and

his sudden death could upend the battle to helm the theocratic regime.

“There’s a lot of money and power at stake when Khamenei dies,” Vatanka

said.

So far, Khamenei has chosen not to name or suggest a likely successor,

preferring to keep it as an open question. Raisi wore a black turban, symbolic

of those who are descendants of the Prophet Muhammad.

“There is a big void with Raisi gone, not just in terms of presidential

candidates but also, even more importantly, in terms of succession to the

supreme leader,” Aniseh Bassiri Tabrizi, an Abu Dhabi-based senior analyst at

the security consultancy Control Risks, told NBC News.

Raisi’s shocking death comes at a time of vulnerability for Iran, even as it forges deeper ties with Russia and China. More generally, it could add an “increased perception of vulnerability” of Iran in Western eyes, Tabrizi said.

“That will affect their negotiating position,” she added, whether that’s

“on nuclear issues or, generally speaking, on negotiations with the West.”

Tehran has accelerated its

nuclear program since the U.S. withdrew from a landmark

agreement capping its activities and has now pushed far beyond the restrictions

imposed in that deal, enriching uranium close to the levels needed to build

nuclear weapons, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency.

Meanwhile, it is supporting a number of proxy

forces fighting Israel, and in some cases American forces, across

the region: from Hamas in Gaza and Hezbollah in Lebanon to the Houthis in Yemen

and fighters in Iraq and Syria.

The situation escalated last month after a suspected Israeli bombing of a

consular building in Damascus, Syria, killed two Iranian

generals. Iran’s unprecedented direct response of 300 missiles and drones fired at

Israel brought the rivals closer to a wider war that neither

appeared to want.

Raisi “was not a strong driving force of any particular line on Iranian

foreign policy, and as a result, his absence is not going to have an impact on

that,” said Trita Parsi, executive vice president of the Quincy Institute for

Responsible Statecraft, a Washington-based think tank.

Iran is in a military standoff with Israel, its regional rival, whose

prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, is seen on a billboard in Tehran this

month. However, his death “is going to create some problems for the regime

internally,” according to Parsi, not only “intensifying the rivalry over

who will take over the supreme leadership” but also possibly weakening Iran’s

attempts to limit attacks by its proxy militias on American forces.

If Iran’s sudden succession quandary causes “some sort of a paralysis,

even briefly, it could lead to a scenario in which Iran’s control over these

militias is weakened,” he said. “And they may actually begin anew their attacks

on U.S. troops and bases.”

It’s clear Iran wants to convey an air of stability and strength.

Khamenei enacted Article 131 of the Constitution, giving Vice President

Mohammad Mokhber power and mandating elections within 50 days, while launching

five days of mourning featuring public funeral processions in major cities that

began Tuesday.

“The Iranians will certainly try to present this as nothing changing,”

said Michael Stephens, a senior fellow at the Foreign Policy Research

Institute, a Philadelphia-based think tank. “Mokhber isn’t really well-known,

so they can paint any image onto him that they like, essentially.”

Raisi was rivaled by many in the Iranian diaspora. On his inauguration,

in August 2021, the National Council of Resistance of Iran held a protest in

London.Adrian Dennis / AFP via Getty Images

It’s unclear who Raisi’s successor might be, owing to the opaque nature

of Iran’s political system. Hard-liners have assumed dominance of all major

facets of Iranian power, and the clerical elite tightly controls who is allowed

to run in its elections — disbarring moderates at recent ballots in March.

Keen Iran-watchers expect Mohsen Rezaee, former head of the powerful

Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, and former Central Bank governor Abdolnaser

Hemmati to stand again, as they did in 2021.

Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, current speaker of the Iranian Parliament, “is

the most prepared candidate,” according to the London-based

diaspora news website IranWire. Meanwhile, “Mokhber will certainly

throw his hat in,” Gregory Brew, an analyst at the New York consultancy Eurasia

Group, wrote on X.

A new vote “will bring some dilemmas for the regime’s top leaders: How

open a field will they allow?” Rob Macaire, former British ambassador to

Iran, wrote in an Atlantic Council

briefing. “Would they prefer a cleric, who might be seen as a

potential contender to take over from Khamenei in due course, or a technocrat?”

Though thousands gathered for the funeral, the mourning period was more

muted than those for other prominent Iranian figures.Ata Dadashi / Fars News

Agency via AP

For many Iranians, Raisi was a hated figure, owing to his role

overseeing mass executions in the 1980s — which earned him the nickname the

“Butcher of Tehran” — and his more recent, brutal crackdown on protesters demonstrating

against Iran’s conservative clothing restrictions for women.

Turnout for the March elections was just 41%, the lowest in modern

history. And public mourning for Raisi has been far more muted than for other

officials, according to Reuters reports from the region, with many shops

staying open. Meanwhile, there were scenes of celebration among the Iranian

diaspora in London and elsewhere.

“Many families have placed Raisi near the top of the list of officials

they wished to see brought to justice for the government’s most egregious

crimes,” said Tara Sepehri Far, a researcher with Human Rights Watch.

But any hopes that Raisi’s death may open the way for a less hard-line

supreme leader will very likely be disappointed, Parsi at the Quincy Institute said.

“The main candidates right now, as at least the ones that have publicly

spoken, are not necessarily less hawkish than Raisi,” he said. “On the

contrary, many of them are considered to be more so.”

Rights advocates said there was a danger the Iranian government could

try to exploit the president’s death as a rationale for ratcheting up

repression of peaceful dissent.

“As the state scrambles to maintain its grip on power, the international community must remain vigilant and responsive to any potential escalation in the crackdown on civil society in Iran,” Hadi Ghaemi of New York-based Center.

Iran has several research sites, two uranium mines, a research reactor, and uranium processing facilities that include three known uranium enrichment plants.

Commencing in the 1950s with support from the United States (under the Atoms for Peace program), Iran's nuclear program was initially geared toward peaceful scientific exploration. In 1970, Iran ratified the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), subjecting its nuclear activities to IAEA inspections. After the 1979 Iranian Revolution, cooperation ceased and Iran pursued its nuclear program clandestinely.

An investigation by the IAEA was launched as declarations by the National Council of Resistance of Iran in 2002 revealed undeclared Iranian nuclear activities. In 2006, Iran's noncompliance with its NPT obligations moved the United Nations Security Council to demand Iran suspend its programs.

In 2007, the United States National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) stated Iran halted an alleged active nuclear weapons program in 2003.[4] In November 2011, the IAEA reported credible evidence that Iran had been conducting experiments aimed at designing a nuclear bomb, and that research may have continued on a smaller scale after that time. On 1 May 2018 the IAEA reiterated its 2015 report, saying it had found no credible evidence of nuclear weapons activity after 2009.

Operational since September 2011, the Bushehr I reactor marked Iran's entry into nuclear power with Russia's assistance. This became an important milestone for Rosatom to become the largest player in the world nuclear power market.bAnticipated to reach full capacity by the end of 2012, Iran had also begun constructing a new 300 MW Darkhovin Nuclear Power Plant and expressed plans for additional medium-sized nuclear power plants and uranium mines in the future.

Despite the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) aimed at addressing Iran's nuclear concerns, the U.S. withdrawal in 2018 prompted renewed sanctions, impacting diplomatic relations. The IAEA certified Iran's compliance up until 2019, but subsequent breaches strained the agreement. In a 2020 IAEA report, Iran was said to have breached the JCPOA and faced criticism from signatories.

In 2021, Iran faced scrutiny regarding its assertion that the nuclear program was exclusively for peaceful purposes, especially with references to growth in satellites, missiles, and nuclear weapons.

In April 2022, Atomic Energy Organization of Iran head Mohammad Eslami announced a strategic plan for 10 GWe of nuclear electricity generation.

In October 2023, an IAEA report estimated Iran has increased its uranium stockpile twenty-two times over the 2015 agreed JCPOA limit.

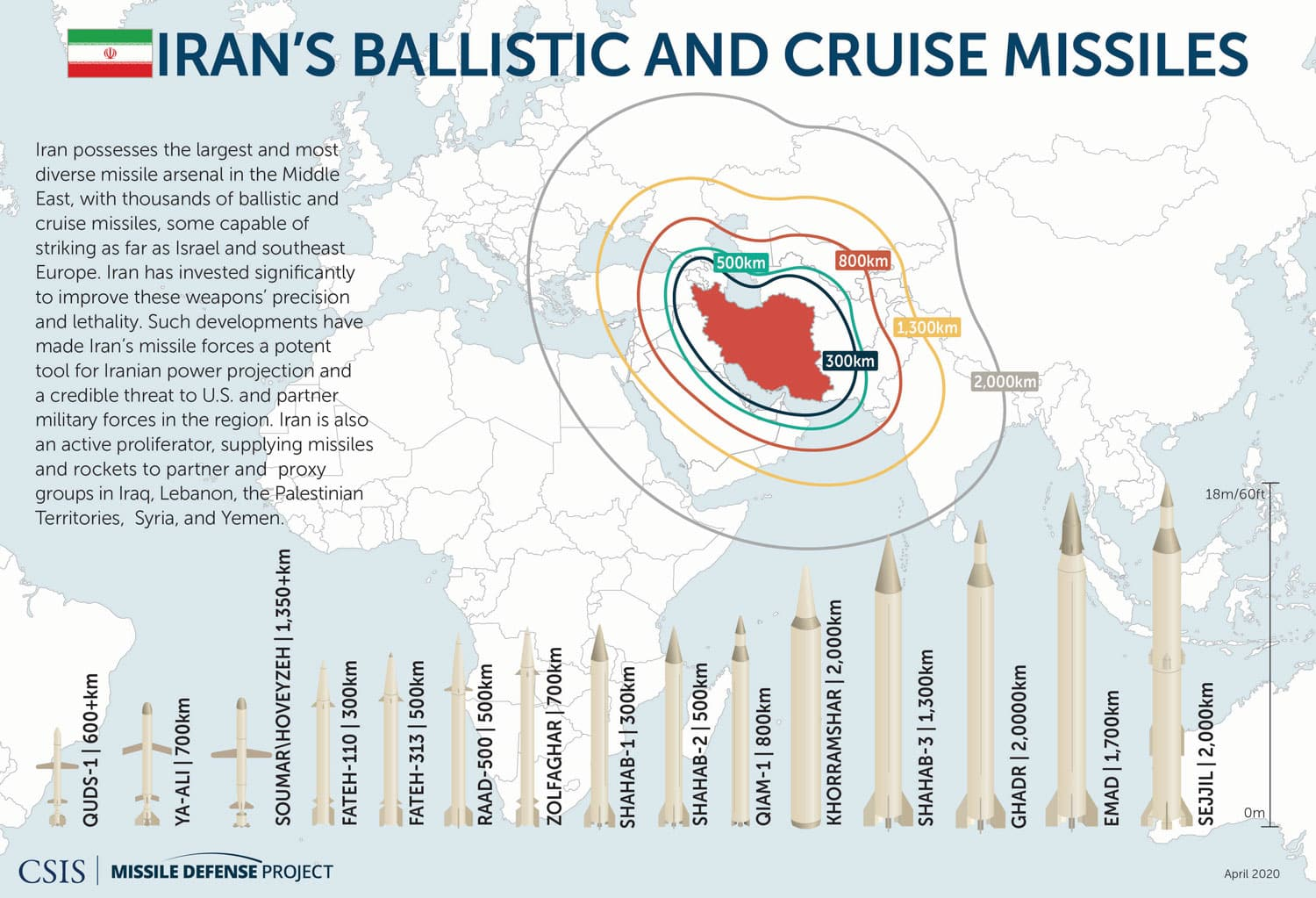

Irans Missile Programme.

Iran possesses the largest and most diverse missile arsenal in the Middle East, with thousands of ballistic and cruise missiles, some capable of striking as far as Israel and southeast Europe. For the past decade, Iran has invested significantly to improve these weapons’ precision and lethality. Such developments have made Iran’s missile forces a potent tool for Iranian power projection and a credible threat to U.S. and partner military forces in the region. Iran has not yet tested or deployed a missile capable of striking the United States but continues to hone longer-range missile technologies under the auspices of its space-launch program.

Iran is also a major hub for weapons proliferation, supplying partner/proxy groups such as Hezbollah and Syria’s al-Assad regime with a steady supply of missiles and rockets, as well as local production capability. Since 2015, Iran has provided Yemen’s Houthi rebels with increasingly advanced ballistic and cruise missiles, as well as long-range unmanned aerial vehicles. Most recently, Iran has been equipping Shiite militia groups in Iraq with rockets and other small projectiles for use against Iraqi and U.S. military and diplomatic facilities.

Source : Irans Missiles.

Comments

Post a Comment