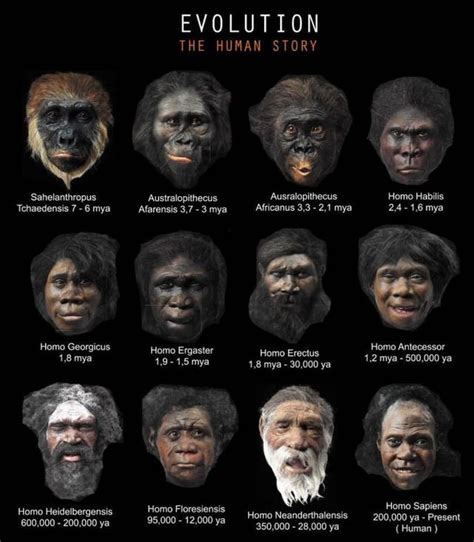

How old is human evolution - There is no single person from which humans evolved - Multiple species evolved in different parts of earth, they interbred, leading to the last known link Homo Sapien.

How old is human evolution - 3.4 million years, Or just 300,000 years or just 30,000 years?

Various theories float about human evolution dating as scientists and archaeologists make fresh discoveries of footprints and bones and do carbon dating. Ape to Man is replaced by a bushy family tree

The Tangled Tree: Unraveling the Complex Web of Human Evolution

A journey through millions of years reveals our ancestry was far messier—and more fascinating—than we ever imagined

By TN Ashok - November 29, 2025

Based on various research findings by scientists and archealogists.

The fossilized foot lay in the Ethiopian soil for 3.4 million years, waiting. When scientists finally unearthed it in 2009 at a site called Burtele, they expected to find yet another relic from Lucy’s world—that famous Australopithecus afarensis who became the poster child for human evolution. Instead, they discovered something that would force a fundamental rethinking of our family tree.

The Burtele foot belonged to someone else entirely. Someone who lived at the same time as Lucy, in the same place, but climbed trees with an opposable big toe like a thumb. According to a study published this week in Nature, researchers have now confirmed this foot belonged to Australopithecus deyiremeda—a previously unknown species that shared the ancient African landscape with our famous ancestor.

“Now we have much stronger evidence that, at the same time, there lived a closely related but adaptively distinct species,” says John Rowan, an assistant professor in human evolution at the University of Cambridge who wasn’t involved in the study.

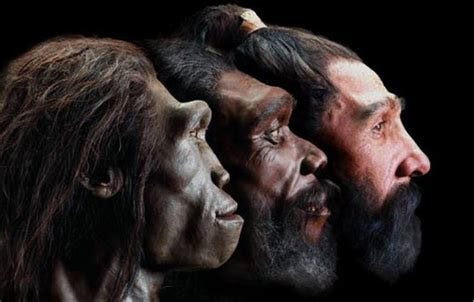

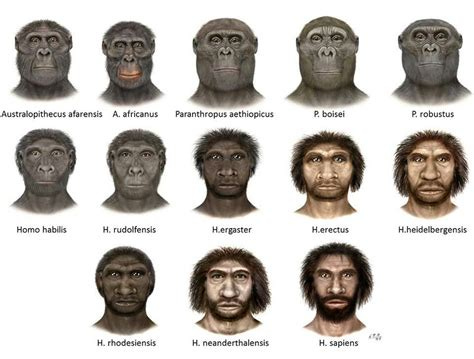

The discovery shatters the linear narrative of human evolution—the old “march of progress” from ape to human—and replaces it with something far more intriguing: a bushy family tree where multiple human relatives coexisted, competed, and occasionally interbred across millions of years.

Darwin’s Revolutionary Idea

The story begins on November 24, 1859, when Charles Darwin published “On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection.” The book sold out immediately, igniting a firestorm of controversy that continues to this day. Darwin’s revolutionary concept was elegantly simple: populations evolve through natural selection, where organisms with advantageous traits survive to pass those traits to offspring.

But Darwin was careful about one thing—he barely mentioned human evolution in his first book. As he wrote to Charles Lyell, “I do not discuss origin of man.” It wasn’t until 1871, with “The Descent of Man,” that he directly addressed our species’ origins from ape-like ancestors.

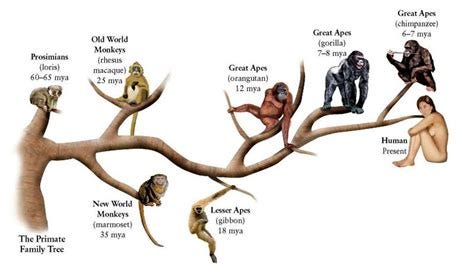

Darwin never claimed, as Victorian critics insisted, that “man was descended from the apes.” Modern scientists view such statements as oversimplifications. Rather, humans and great apes share a common ancestor that lived between eight and six million years ago in Africa.

The Deep Roots of Our Family

The evolutionary journey that created modern humans stretches back far beyond Darwin’s wildest speculations. Life itself began approximately 4 billion years ago with simple single-celled organisms called protocells. These primitive cells possessed only RNA, which gradually evolved into the more stable DNA molecule we carry today.

Fast forward through billions of years of evolution—through the emergence of complex cells, the transition from sea to land around 500 million years ago, and the rise of mammals after the dinosaurs went extinct 66 million years ago. The story of human evolution specifically begins much more recently, though the exact timeline remains a subject of intense debate.

The human lineage branched from the line leading to great apes somewhere between eight and six million years ago. One of our earliest-known ancestors, Sahelanthropus, began the slow transition from ape-like movement about six million years ago. But Homo sapiens—anatomically modern humans—wouldn’t appear until about 300,000 years ago.

“The long evolutionary journey that created modern humans began with a single step—or more accurately—with the ability to walk on two legs,” notes the Smithsonian Institution’s research on human evolution.

A Crowded Landscape

For decades, scientists believed human evolution followed a relatively straight path: one species evolving into the next in an orderly progression. Lucy’s species, Australopithecus afarensis, was considered the sole ancestor of later hominids during her era, roughly 3.4 to 2.9 million years ago.

The Burtele foot discovery obliterates that neat narrative. Not only did A. deyiremeda live alongside Lucy, but the two species likely carved out different ecological niches. Lucy’s kind roamed the open grasslands, walking upright. The deyiremeda spent more time in forests, using their grasping feet to navigate trees.

“These differences meant that they were unlikely to be directly competing for the same resources,” explains Ashleigh L.A. Wiseman, an assistant research professor at Cambridge’s McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research. The newly discovered teeth suggest A. deyiremeda maintained a more primitive diet of leaves, fruit, and nuts compared to Lucy’s more varied menu.

But Lucy and her tree-dwelling contemporary were just two threads in an increasingly complex tapestry. Scientists currently recognize between 15 and 20 different early human species. Most left no living descendants—extinct branches on our family tree.

During the period from 4.3 million to 1.98 million years ago, several australopith species coexisted. Later, between 2.8 million and 1.65 million years ago, early members of our own genus, Homo, appeared on the scene. The oldest known remains of Homo date to about 2.8 to 2.75 million years ago in Ethiopia—yet evidence of stone tool-making dates back to 3.3 million years ago in Kenya, predating the earliest known Homo by hundreds of thousands of years.

When Cousins Became Relatives

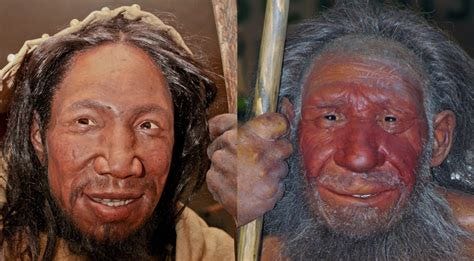

Perhaps the most startling revelation in recent decades concerns not the distant past but relatively recent history. Around 50,000 years ago, when anatomically modern humans—Homo sapiens—began migrating out of Africa into Eurasia, they encountered other human species already living there.

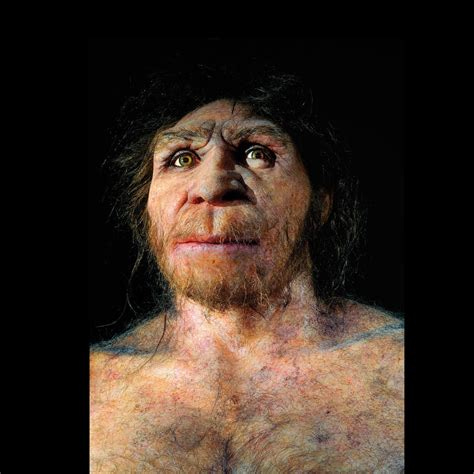

In caves scattered across Europe and Asia, they met the Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis), our closest known evolutionary cousins. Neanderthals had been thriving in these regions for hundreds of thousands of years, with fossils dating back at least 200,000 years. They manufactured sophisticated tools, developed spoken language, created art with natural pigments, buried their dead, and likely practiced traditional medicine.

“Neanderthals might have overlapped with the Denisovans across Asia for over 300,000 years,” notes Chris Stringer, a human evolution researcher at London’s Natural History Museum.

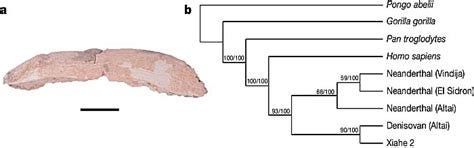

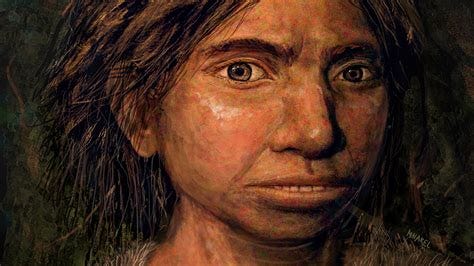

The Denisovans—a mysterious group identified primarily through DNA from a handful of bone fragments and teeth found in Siberia’s Denisova Cave—represent another chapter in this story. First identified in 2010, Denisovans lived across vast stretches of Asia, from Siberia to the Tibetan Plateau and Southeast Asia.

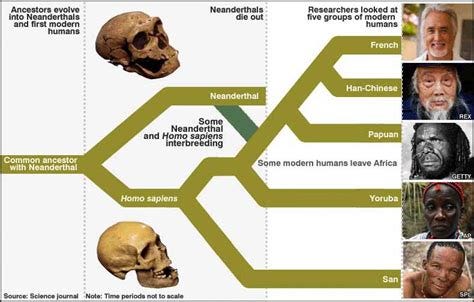

What happened when these human groups met? For decades, scientists assumed different human species remained reproductively isolated. The genetic evidence tells a very different story: they interbred. Frequently.

Today, most people of non-African descent carry 1-4% Neanderthal DNA in their genomes. Some Southeast Asian and Oceanian populations carry 4-6% Denisovan DNA. In 2018, scientists reported finding the remains of a teenage girl who lived about 90,000 years ago—her mother was a Neanderthal, her father a Denisovan. The discovery of this first-generation hybrid suggests interbreeding between human groups was far more common than previously imagined.

“Neanderthals and Denisovans may not have had many opportunities to meet,” says Svante Pääbo, who led the study. “But when they did, they must have mated frequently—much more so than we previously thought.”

These ancient liaisons left lasting marks on our genomes. Neanderthal genes helped modern humans develop resistance to European diseases. Denisovan genes helped populations adapt to high-altitude living, allowing people to cross the Himalayas and thrive in oxygen-poor environments.

Recent research reveals an even deeper layer of complexity. The ancestors of Neanderthals and Denisovans themselves interbred with a “superarchaic” population that had been separated from other humans for about 2 million years. Additionally, 4% of the Denisovan genome comes from yet another unknown archaic human species.

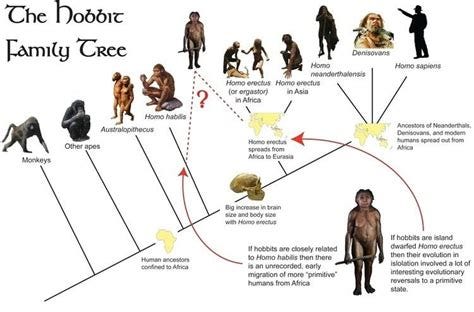

The Hobbits of Indonesia

While scientists were piecing together the story of Neanderthals and Denisovans, researchers in Southeast Asia stumbled upon one of the most perplexing discoveries in paleoanthropology. In 2003, in Liang Bua cave on the Indonesian island of Flores, they found remains of a human species that stood barely over three feet tall, with a brain about one-third the size of modern humans.

Homo floresiensis, quickly nicknamed “the hobbit” after Tolkien’s fictional creatures, completely defied expectations. How did these diminutive humans get to an island separated from the mainland by treacherous seas? How did they survive with such small brains? And where did they come from?

The hobbits lived on Flores from at least 100,000 to 50,000 years ago, possibly as long as a million years ago based on stone tools found on the island. Despite their tiny stature and small brains, they made and used sophisticated stone tools, hunted pygmy elephants called Stegodon, and coped with predators including giant Komodo dragons.

Their origin remains hotly debated. Some scientists argue they evolved from Homo erectus populations that reached the island and underwent “island dwarfism”—a well-documented phenomenon where large animals isolated on islands evolve smaller bodies due to limited resources. Others suggest they descended from an even more ancient, already-small ancestor like Homo habilis from Africa.

New fossils discovered in 2024 at the Mata Menge site deepened the mystery. At 700,000 years old, these ancestors of the hobbits were even shorter—standing barely one meter tall. Paradoxically, this means the hobbits actually got slightly taller over time, contradicting the island dwarfism hypothesis.

The story becomes even stranger when we consider that another small-bodied human species, Homo luzonensis, was discovered nearly 3,000 miles away in the Philippines around the same time period. How many small human species were living on Southeast Asian islands? Did they all descend from the same ancestor?

“Did they interact?” Wiseman asks about the various coexisting species. “We will likely never know the answer to that question.”

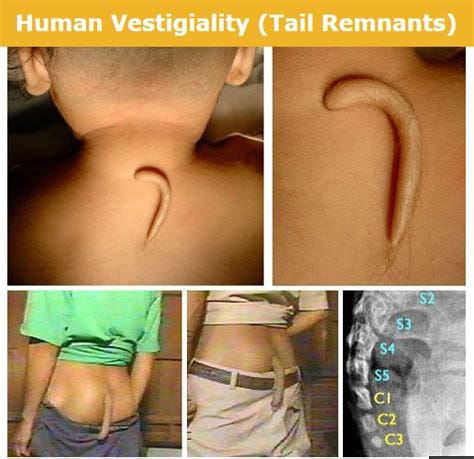

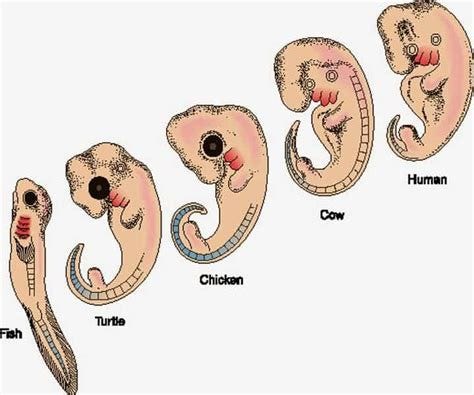

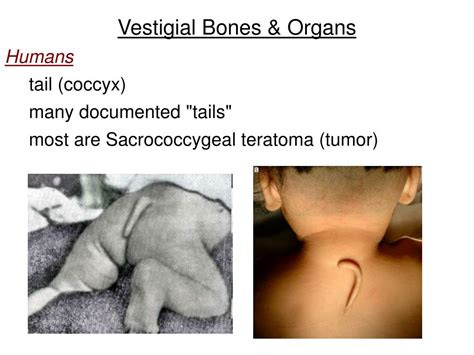

Vestigial Mysteries: The Case of the Missing Tail

Our evolutionary heritage has left traces written not just in fossils but in our very bodies. The human coccyx—the small, fused vertebrae at the base of our spine commonly called the tailbone—represents one of the most cited examples of vestigial features, anatomical structures that have lost their original function through evolution.

All mammal embryos develop a tail at some point. In humans, this tail is present for about four weeks during embryonic development before being reabsorbed by the body. In extremely rare cases—perhaps a few hundred documented worldwide—babies are born with what appears to be a true tail, a small skin appendage extending from the lower back. These structures, which contain adipose and muscular tissue but no bone or cartilage, can be surgically removed.

The coccyx itself, despite being labeled “vestigial,” actually serves important functions. It provides an attachment point for multiple muscles, ligaments, and tendons that form the pelvic floor—essentially keeping our abdominal organs from falling through our legs. It also plays a crucial role in bowel control.

Scientists have recently identified the genetic changes responsible for tail loss in apes and humans. Research published in 2024 found that tailless primates share a specific DNA insertion absent in tailed monkeys. This genetic change occurred approximately 25 million years ago in our shared ancestor with other great apes.

How Old Is Human Evolution?

This question has vexed scientists and the public alike. The answer depends entirely on where you start counting.

If you begin with the first life on Earth, the story is about 4 billion years old. If you start with the split between the human lineage and chimpanzees, it’s about 6-7 million years.

If you’re asking about our species specifically—Homo sapiens—the answer is roughly 300,000 years.

The various australopiths, our early bipedal ancestors, emerged in eastern Africa around 4 million years ago. The genus Homo appeared approximately 2.8 million years ago. Homo erectus, one of the most successful early human species, emerged roughly 1.9 million years ago and persisted for nearly 2 million years, spreading across Africa, Asia, and Europe.

This timeline is measured in millions, not billions, of years—a crucial distinction. While life itself is ancient, the human story is relatively recent in geological terms.

Multiple Theories, One Complex Truth

As the fossil record expands and genetic technologies advance, the debates intensify. Some researchers argue for multiregional evolution—the theory that modern humans evolved simultaneously in different parts of the world from local archaic populations. The dominant “Out of Africa” theory holds that anatomically modern humans evolved solely in Africa and then migrated outward, replacing earlier human populations.

The genetic evidence strongly supports the African origin story, with interbreeding as a significant caveat. We didn’t just replace Neanderthals and Denisovans—we absorbed them, carrying fragments of their DNA into the future.

“Which species were our direct ancestors? Which were close relatives? That’s the tricky part,” explains Rowan. “As species diversity grows, so do the number of plausible reconstructions for how human evolution played out.”

The Lucy-era discovery in Ethiopia exemplifies this complexity. For years, scientists assumed a single hominin species dominated the landscape at any given time. Now we know multiple species coexisted, each adapted to different ecological niches.

“Human evolution wasn’t a straight ladder with one species turning into the next,” Wiseman emphasizes. “Instead, it should be viewed as a family tree with several so-called ‘cousins’ alive at the same time, and each having a different way of surviving.”

The Future of Discovery

Every new fossil discovery rewrites our understanding. The Harbin cranium from China, identified in 2025 as belonging to Denisovans through protein analysis, proved that these mysterious humans had broad faces and massive brow ridges. The Mata Menge fossils from Flores pushed back our understanding of when hobbits arrived on the island and how they evolved.

Advances in ancient DNA recovery have revolutionized the field. From the 430,000-year-old remains in Spain’s Sima de los Huesos cave—the oldest Neanderthal DNA ever recovered—to the genetic mapping of Denisovans known from just a handful of bone fragments, DNA has become our time machine into the deep past.

But genetics has limitations. Dating remains imprecise, with margins of error spanning hundreds of thousands of years. And many crucial fossils—particularly in the tropical regions where early humans evolved—have decomposed beyond the point where DNA can be recovered.

Wiseman cautions against making definitive species assignments without well-preserved skulls and fossils from multiple individuals. While the new Ethiopian research strengthens the case for Australopithecus deyiremeda as a distinct species, “it doesn’t remove all other alternative interpretations.”

What It All Means

The modern picture of human evolution is messy, complicated, and far more interesting than the tidy “ape to human” progression diagram found in old textbooks. Our family tree looks less like a ladder and more like a dense, thorny bush with many dead-end branches.

Multiple human species roamed Earth for millions of years. They made tools, controlled fire, buried their dead, created art, and adapted to environments from tropical forests to arctic tundra to remote islands. Most went extinct, leaving behind only fragmentary fossils and, in some cases, traces in our DNA.

The hobbits vanished around 50,000 years ago, likely shortly after modern humans reached their island.

The Neanderthals disappeared between 40,000 and 24,000 years ago. The last Denisovans probably died out around the same time.

By about 30,000 years ago, Homo sapiens stood alone—the only human species left on Earth.

Or did we? The discovery of unexpected human species on isolated islands like Flores and Luzon raises intriguing possibilities. Could other small, isolated populations have persisted longer than we know? Local legends in Flores speak of the Ebu Gogo—small, hairy cave dwellers similar in description to the hobbits. Could these stories preserve cultural memories of encounters with the last representatives of another human species?

We’ll probably never know for certain. But every year brings new discoveries, new technologies, and new questions. The Burtele foot, lying undiscovered for 3.4 million years, waited patiently for science to catch up. How many other secrets still lie buried in the African savanna, Asian caves, or Pacific islands, waiting to rewrite our understanding of what it means to be human?

As Rowan notes, “As the number of well-documented human-related species grows, so do our questions about our ancestry.” The march of progress has been replaced by a tangled tree—and we’re still learning to read its branches.

Comments

Post a Comment